Introduction

Civic liberties and parliamentary institutions represent one of the major cultural legacies England left to the civilization of the world.

The first document protecting individual liberty and the prototype of the modern Parliament appeared in England as early as the 13th century. However, effective protection against arbitrary power and the first parliamentary regime emerged much later in the 17th.

However, the modern notion of democracy, which implies full political citizenship for everyone (no one deprived of the right to vote) took a much longer time to take route in Britain than elsewhere in the world.

The pioneer of Parliamentarism took the slow road to universal suffrage. As the American claim for independence and liberty showed in the late 19th century, English liberty celebrated by the most famous philosophers (Voltaire and Montesquieu) was more a myth than a reality.

Origins of Parliament and Civil Liberties

In Britain, there is no written constitution to protect civil liberties and define the rules of the political game. Yet, several traditions, constitutional agreements and political conventions exist and constitute the pillars of the regime.

One of those documents is the Magna Carta (Great Charter) granted by King John in 1215 under the pressure of his aristocracy and clergy. This document excluded very early in English history the practice of political absolutism and excessive use of the royal prerogative).

Moreover, after the Magna Carta, no excessive demand for money could be made by the King without the consent of the aristocracy and clergy. British and American tradition of the vote on taxation finds its origin in this event.

Finally, concerning individual freedom, after the Magna Carta, no arrest in prison or punishment could be performed on aristocrats and clergymen without a trial by similar kinds of people, according to the law of the land. It is the starting point of the notion of trial by peers.

Later on, in 1265, Edward I was forced by his aristocracy to assemble (summon) the first Parliament in English history, which took the name of Model Parliament. The very notion of Parliament, from the French word “parler” implies a discussion on every legislative decision and therefore, the possibility for a diversity of opinions.

The English Parliament was the first to include representatives from outside the clergy and aristocracy. It was established in a very pragmatic way, simply for the King needed the support of the whole nation for his military campaigns against Wales, Scotland and France.

Thus, he needed to raise money through taxation. So, before being a full legislative body where the law is made, Parliament rests on the principle of no taxation without political representation.

From its origin, the Parliament started to meet in two separate chambers located in the Palace of Westminster:

- The Upper House or House of Lords, is organized according to the principle of heredity (by birth, not by elections).

- The Lower House or House of Commons, is organized by elections and receiving the representatives of taxpayers and landowners (= the rich).

The Parliamentary institutions founded in the Middle Ages have a paradoxical nature.

The Model Parliament was the first representative political body in Europe, England was called the Mother of Parliament but the right to vote (= the Franchise) and the right to be elected (= Eligibility) were defined as a privilege either of birth or property and money, not as a universal right.

It took several centuries for England to reform this initial trend.

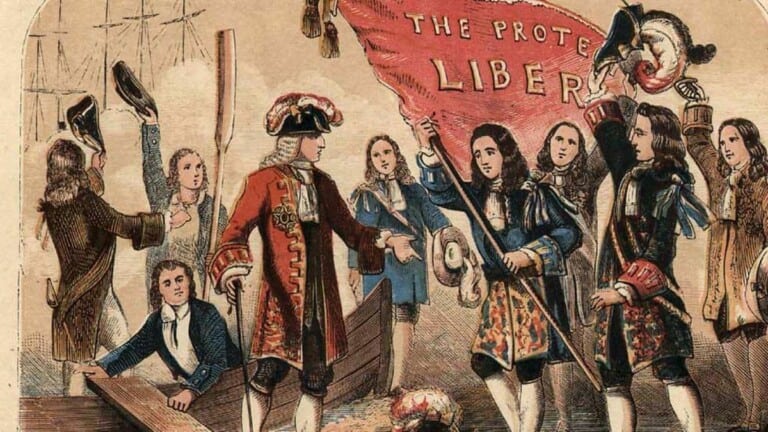

The Glorious Revolution of 1688

In the first part of the 17th century, abuse of authority from the King led to a re-statement of rights whose origins could be found in English history.

At the end of the 17th century, after a period of Civil War and a peaceful revolution, the tradition of parliamentary sovereignty became part of the legal framework of the English constitution.

In 1628, the Parliament opposed a petition of rights to the King, claiming political guarantees against money for Charles I’s European and colonial wars. The King’s refusal to renounce this prerogative led to a civil war and the King’s execution in 1649.

The principle of the petition re-emerged in the events of 1688, called the Glorious Revolution for it was bloodless.

The current King James II was forced to leave the country and was replaced by his daughter Mary and her husband William on the condition that the two would accept a declaration of rights in exchange for the throne.

The contract was instituted: political power against rights. After it was approved, the declaration was known as the Bill of Rights in 1689, which constituted the first constitutional monarchy in the world by stipulating once and for all:

- The King can’t suspend a law voted in Parliament

- The King can’t raise taxes or maintain a permanent army in time of peace without a vote in Parliament.

The new institution created the notion of Government by the leaders of the country’s majority and led to the formation of two political parties alternating in power as the majority and the opposition.

The name of the first party was the Whigs: they supported the new regime and represented the world of business and commerce. In the 19th century, the Whigs became the Liberal Party.

The second party was the Tories, who supported a more authoritarian definition of the monarchy. They represented the class of agricultural landowners. In the 19th century, the Tories became the Conservative Party.

In the field of individual rights, before the Glorious Revolution, a piece of legislation passed in 1679 called the Habeas Corpus aimed at protecting subjects against royal absolutism alongside the lines first defined by the Magna Carta.

The Habeas Corpus banned arrest and detention without trial but freedom from custody could only be obtained after came on an amount of money, given as a guarantee and called a bail.

Therefore, by the end of the 17th century, England had become the first representative government in Europe. The King’s right to suspend legislation (to refuse to give assent to a bill accepted by both Houses of Parliament) became purely theoretical: this right of veto was last exercised in 1707.

Later on, the tradition of cabinet government and the position of Prime Minister progressively emerged and later became an unquestionable right of the British people.

The P.M. was the leader of the majority party in the House of Commons. He became the real head of Government: British Kings were said to reign but not to rule.

Yet, this perfect picture of British liberties needs to be corrected by several remarks.

The myth of English liberty

In the 18th century, apart from the Bill of Rights and the Habeas Corpus, no constitution protected British subjects from political abuses. The King had the full power of creating Lords (= Peers). He therefore influenced legislation.

In terms of elections, out of 8 million inhabitants, only 160,000 were voters. Until the middle of this century, parliamentary debates were secret but before 1872, ballots were not secret. Thus, the King could use corruption and intimidation to buy votes.

Radical agitators criticized the fact that the British were subjects instead of full citizens: parliamentary reforms became more and more advocated both inside and outside Britain:

- The major group of protesters were the American colonists who were not represented in Parliament for they lived outside Britain but who had to pay taxes to the British government.

- The second major group of protesters was the middle-class dissenters who were refused access to public jobs for religious reasons.

British people had to wait until 1832, i.e. several decades after the American and French revolutions to witness some partial changes in their system of representation.

Under popular pressure, the 1832′ Reform Act abolished unrepresentative seats in Parliament to increase representation. For instance, the medieval village of Dunwich, which had disappeared from the map still returned an MP to Parliament and the village of Old Sarum had 7 voters who elected 2 MPs!

At the same time, the Act distributed new seats to represent the population of recent industrial centres like Birmingham or Manchester but even after 1832, the numbers of voters represented no more than one-fifth of the adult male population.

It was only in the second part of the 19th century that the progressive extension of the franchise opened Parliament to the working class.

Full universal suffrage for men over 21 was finally reached in 1918 but paradoxically, this very late measure was at the same time an early victory for the cause of women’s rights.

British women received the right to vote in 1918, i.e. some 38 years before French women. Voting parity for all citizens, male or female, was finally decided in 1928.

From the experience of the Middle Ages and thanks to the institutional changes triggered off by the Glorious Revolution, British political culture inspired most modern parliamentary regimes.

However, the long absence of truly democratic representation was one of the origins of the American Revolution and led to the definition of new political models.

Synopsis » From the Reformation to the birth of the American nation (1534-1776)

- The Reformation in the British Isles

- English Expansionism

- The Glorious Revolution of 1688

- The American colonies : Religion and Politics

- USA: Birth of a Nation