Introduction

Scotland was never conquered by England. There were attempts but they failed. At the end of the 13th century, the wars of independence began.

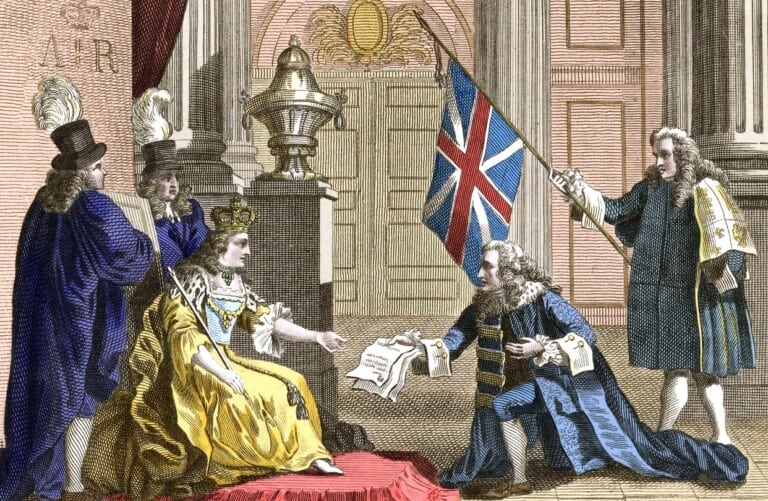

On May 1st 1707, the Act of Union was ratified between England and Scotland: the Scottish Parliament and the English Parliament were suspended. They created the British Parliament and formed Great Britain by the Union of Scotland and England.

At the time, Scotland was already a protestant country (the Reformation came in the 16th century, before then she was catholic). As England was also protestant, the two nations grew closer.

The Queen chose several men to represent Scotland and England in a commission to discuss the terms of the Treaty of Union. Several Acts and events precipitated the Union.

1698 – 1699: expeditions to Darien

It was a total failure for the Company of Scotland :

- Scotland lost trading opportunities with France (due to the Reformation),

- the Navigation Acts (1660-1663) prevented Scotland from trading with English colonies.

In England, the East-Indian Company had monopole and money. Hence, Scotland wanted the same: that is how the Company of Scotland was set up in 1695. Its full name was “Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies”.

The East Indian was not very happy and put pressure on English financiers who wanted to provide money to the capital of the Company of Scotland. The financiers finally withdrew and the Scots had to provide money themselves: a multitude of people giving little money.

The Company of Scotland established a trading post in America: Darien, in the Isthmus of Panama. 1698 saw the 1st expedition to Darien. It was a terrible failure for many people died during the journey and by fighting against the Spaniards already settled there.

The 2nd expedition was also a failure and the people who had invested in the enterprise were ruined, just like the company. After that experience, the Scots thought the best thing would be a union with England (no more Navigation Acts and access to colonies trading).

Lire la suite