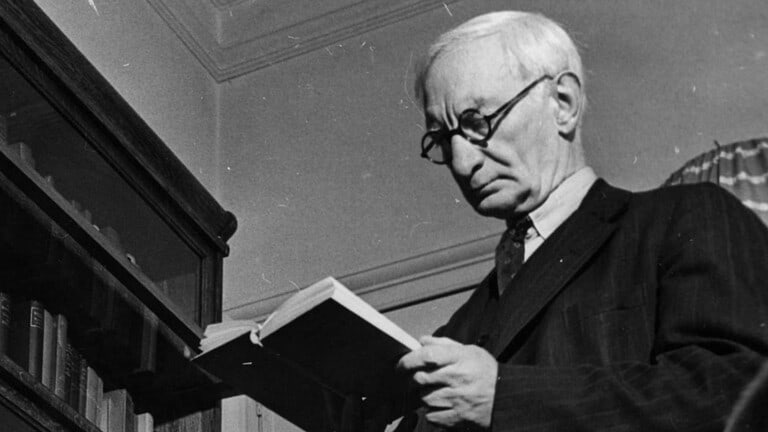

William Beveridge

William Beveridge was born in 1879 and he became a social worker in the East End of London in 1903. Later, he visited Germany to see for himself the system of social insurance introduced by Bismarck.

Beveridge became a journalist, writing mainly on social policy. He was noticed by Churchill (still a Liberal at that time) and in 1908, Beveridge became a civil servant at the Board of Trade.

Over the next three years, he worked on a national system of labour exchanges, which were introduced by the Liberal Government of Lloyd George. This measure only covered 2.75m men, one in six of the workforce.

Beveridge remained a civil servant for the duration of World War I and after the war, he became the Director of the London School of Economics (LSE). He continued academic work at the Universities of London and Oxford.

In June 1941, he was asked to chair an interdepartmental committee on reconstruction problems and on the coordination of existing schemes of social insurance.

At this time, the social security “system” was in a confused state: 7 Government departments were involved in providing various cash benefits to some people.

The terms of reference were:

To undertake, with special reference to the inter-relation of the schemes, a survey of the existing national schemes of social insurance and allied services, including workmen’s compensation, and to make recommendations. (Beveridge, Beveridge Report : Social Insurance and Allied Services, 1942)

The Beveridge Report

It had been thought Beveridge would just tidy up the existing schemes but in fact, he came up with a brand-new scheme.

In December 1941, he produced a preliminary paper entitled Heads of a Scheme, setting out ideas and assumptions, which were repeated in a slightly amended form in the Report itself:

Three Assumptions : no satisfactory scheme of social security can be devised except on the following assumptions :

1. Children’s allowances for children up to the age of 15 or if in the full-time education up to the age of 16;

2. Comprehensive health and rehabilitation services for prevention and cure of disease and restoration of capacity for work, available to all members of the community;

3. Maintenance of employment, that is to say avoidance of mass unemployment

Beveridge

These words take us a long way from the Means Test of the 1930’s and private insurance. In Beveridge’s view, benefits should become rights.

What was revolutionary was not that the system was based on “insurance”, backed by the state, but that it would be universal, signifying an end to all means tests.

However, if insurance was to provide the basis for benefits, then children’s allowances would be paid whether the parents were in work or not. If children’s allowances were means tested, then the low-paid with large families would be better off out of work than working unless benefits were very low. This is the problem of the so-called “wage benefit overlap“.

It is interesting here to go back to Rowntree’s investigations in 1899 to see how families with many children were often penalised if the wages coming in were relatively low.

Since Beveridge and others believed the birth rate was falling and thus the country would, in the long term, suffer from this decline, his ideas were also coloured by a desire to encourage women to have children and not to penalise them for so doing.

Beveridge was not the first to raise the questions of children’s allowances: Rowntree himself and others had advocated their introduction before the War and even in the period 1940-1941, an inter-Party group was formed to accelerate their introduction.

When the Report was published on December 1st 1942, it received massive approval. On the night before publication, there was even queues outside HMSO (His Majesty’s Stationery Office) branches to buy it. Sales reached 6 figures before the end of the year.

The Home Intelligence Unit of the Ministry of Information said the Report was welcomed with almost universal approval as the first real attempt to put into practice talk about the “new post-war world”.

Beveridge wages War in his Report on five giants: Disease, Ignorance, Squalor, Idleness and Want i.e. poor health, poor education, poor living conditions, unemployment and poverty.

In the beginning, Beveridge briefly explains the reasons why he had come to the conclusions he presents in his Report. He points out that the various schemes in existence have grown piecemeal over the years.

Each problem had been dealt with separately: “The first task of the Committee has been to attempt for the first time a comprehensive survey of the whole field of social insurance and allied services, to show just what provision is now made and how it is made for many different forms of need”.

Beveridge does not begin with open criticism of the status quo. The situation in Britain, he says, is “hardly rivalled in other countries of the world”. However, Britain does fall short in the field of medical services “both in the range of treatment which is provided as of right and in respect of the classes of persons for whom it is provided” and in the field of cash benefits “for maternity and funerals and through the defects of its system for workmen’s compensation”.

Beveridge adds that the “limitation of compulsory insurance to persons under a contract of service and below a certain remuneration if engaged in non-manual work is a serious gap”. He advocates therefore closer coordination which would help beneficiaries and indeed cost less in administrative costs.

He then goes on the point out three guiding principles of recommendations and signals the way to freedom from want. Later, he indicates what he means by the notion of “social insurance” which underpins the Report: “It implies both that it is compulsory and that men stand together with their fellows.

The term implies a pooling of risks…”. The concept behind it is innovative: universality and national solidarity – instead of each person, each category of workers having a separate system or even no system of cover, all workers are treated in the same way, in exchange for their contributions.

The Report then goes into great detail about the proposed level of contributions and is rather technical. The conclusion to the Report presented immediately before a large section of appendices is entitled “Planning for peace in war”.

Beveridge points out the likely arguments supporters or detractors, on one side or another, of his Report will make. He answers them by situating the Report in its historical (and historic) context and as a fine war aim to set out, through courage and faith, in a spirit of national unity, as a victory for justice.

The impact of the Beveridge Report

Many people misunderstood the Beveridge Report, thinking it proposed free welfare benefits when it fact it promised insurance benefits, based on insurance contributions and children’s allowances based on taxation since plainly “you don’t get something for nothing”.

An illusion was created that in some way, this was going to be a generous gift from the state to all individuals. This misunderstanding was in part cultivated by Beveridge himself. Yet if one looks closely at the text, he refers to providing people with a “subsistence level”, with the onus on them to work to improve their lot.

To understand the impact of the Beveridge Report, one must look back to the inter-war years. Then, the question of the myth of national solidarity during the hard months marked by the threat of invasion and the Blitz needs to be considered.

Divisions in the country may have been forgotten at a time of national crisis, but the basic problems still existed: injustice, inequality, and indifference were still prevalent, especially in many industrial cities of the North, Glasgow, South Wales, and the East End of London. And even in the superficially or affluent rural areas, agricultural workers were hardly well-off.

Beveridge’s ideas were in tune with current thinking and that’s the reason for its success. Many thought the Report was going to lead to radical “utopian” social change. Those witnesses called by the Committee also broadly supported the radical change. Also, the need to modernise, coordinate, ration, and centralise during the War sapped traditional ideas of individuality and a small role for the State.

Beveridge had leaked much of what was in the Report, so there was a great expectation. Sometimes his leaks were unfortunate: “[the report] would take the country halfway to Moscow”. This guaranteed him and his Report a cool reception from the Government.

Nevertheless, Montgomery’s success at the battle of El Alamein had just taken place and this victory, for the first time, over the so-called “invincible Germans”, caused church bells to ring out on November 15th, 1942, just before the publication of the Report, so it could be said to have arrived at a propitious moment for the country.

The public reaction was enthusiastic but other reactions were mixed. Some did not believe in all this talk of a “new Jerusalem”, such as Sir John Forbes Watson, Director of the Confederation of British Employers (CBE) and J. S. Boyd, Vice-President of the Shipbuilders Employers’ Federation, who thought the measures could not be afforded.

Churchill’s position was perhaps surprising: he was against the Report, preoccupied as he was with winning the War, and thus with the foreign policy before home policy. Churchill had defined the terms for the Coalition in the following terms: “everything for the war, whether controversial or not, and nothing controversial that is not bona fide needed for the war”.

Also, Churchill wondered, with others, if it could be afforded. In his opinion, it was impossible, financially speaking, immediately.

Conservatives were unsuccessful at by-elections, as they gave the impression they were against it. He was obliged eventually to make a speech in 1943 modulating his position and claiming the credit for inaugurating a reflection on the question of National Insurance.

A Whitehall Committee was set up to look into the implementation of the Report. Then, White Papers were produced on the subject of a National Health Service, Employment Policy, and Education, the latter leading to the 1944 Education Act.

Therefore, even though it was the Labour Government of 1945 that introduced the Welfare State, preparatory work had been done by Churchill’s Coalition Government, which of course included many Conservatives.

Synopsis » Inequalities in Great Britain in the 19th and 20th centuries

- Ante Bellum, Inter Bella : Legislation and the Depression

- Electoral inequalities in Victorian England: the Road to Male Suffrage

- Inequalities in Britain today

- Inequality and Gender

- Inequality and Race

- More electoral inequalities : the Road to Female Suffrage

- The Affluent Society : poverty rediscovered?

- The Beveridge Report: a Revolution?

- The Poor Law Amendment Act (1834)

- The Thatcher Years : the individual and society

- The Welfare State: an end to poverty and inequality ?

- Victorian philanthropy in 19th century England