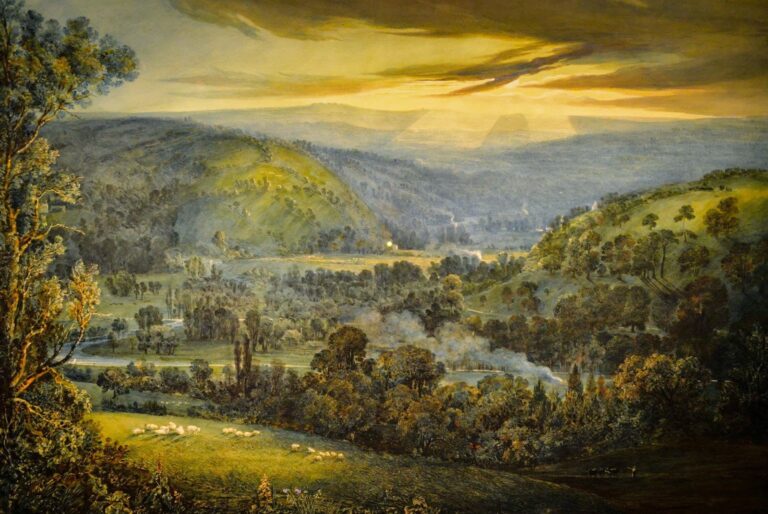

Utopia is based on the concept of rest, linked up with dreams. In Rip Van Winkle (1819) by Washington Irving, the character falls asleep for 20 years and wakes up in the middle of nowhere, in the theme of “suspended animation”. When Rip wakes up, he has missed the American Revolution: he is a stranger in his own land because of the lapse of time due to an irrational event.

To rip is to tear. He rips the curtains of time. RIP also means “rest in peace”. It symbolises death and resurrection. Rest is therefore the framework of the novel, along with the importance of Marxism. The author cannot help infusing his own beliefs into his programmatic vision. William Morris is “moved by compassion for the working class”.

William Morris’s socialism, inspired by scientific Marxism, emphasises fellowship, happiness, personal fulfilment through work and art, and the role of education in the socialist process. The future of revolution depends on the success of education. His socialism respects individuality and no repression of the varieties of human nature.

It clouds the issues: it is more a matter of time than a place. Nowhere is England and the reporter is addressing an imaginary audience. “Rest” has several meanings. An epoch is a period, a parenthesis in history, just a time-lapse in the future.”Some chapters’ are a few fragments from future history, limited.

Rest and Unrest

Unrest represents social unrest, in the capitalist society. Contrariwise, rest breaks from capitalism, it is a necessary death resulting in resurrection and regeneration, a vital revival after a long period of social turmoil. Rest suggests a historical ordeal, relief and respite after a long struggle. It qualifies Marxist influences.

The first leitmotiv is pleasure. Then it gives way to rest and peace. Words are related to each other. Page 44 shows rest on happiness, peace and dreams. The notion of dream permeates the narrative. The guest is transported to the world of 2103.