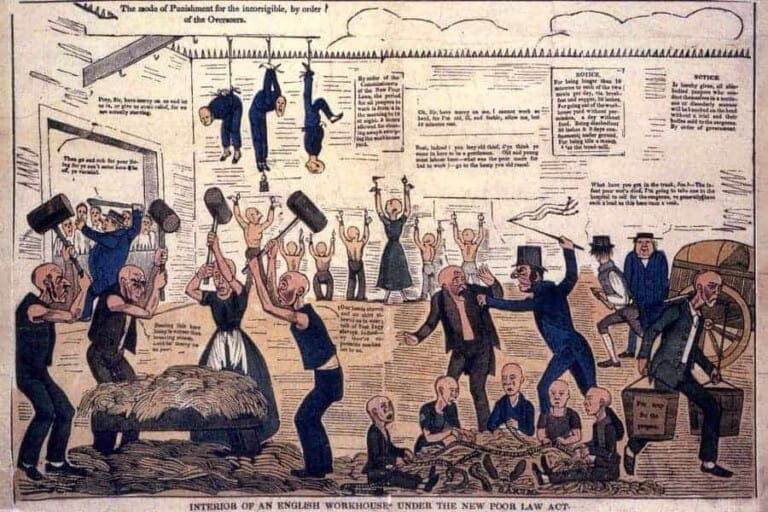

Two approaches seem to characterize the second half of the 19th century: on the one hand, Victorian philanthropy, designed essentially to reward those worthy of salvation and, on the other hand, a movement away from assistance towards self-help, the Cooperative Movement, Friendly Societies including Oddfellows, Trade Unions…

Charity was widespread during the 19th century though the actual amount distributed is difficult to estimate. It is claimed by William Howe, who produced surveys of London charities, that “the income of the London charities… (reached)… £2,250,000 in 1874-75 rising to £3,150,000 in 1893-94“. This was approximately one-third the figure spent by the Poor Law authorities at the time.

There have even been claims that charity exceeded State expenditure on the poor. Of course, not all charitable donations were intended for the poor.

Middle-class philanthropy was sometimes to be found in certain employers who attempted to look after the welfare of their workers: Cadbury in Birmingham, Lever on Merseyside, and Colman in Norwich are examples of this.

In 1869, the Charity Organization Society (C.O.S.) was set up to organize charities to maximize the charitable effects and to minimize any demoralization of the poor, by encouraging undeserving people to remain recipients of relief.

One of its leading lights was Octavia Hill, a leading housing reformer. Beneficiaries of church-sponsored charities would be expected to attend church or send their offspring to Sunday School in exchange for help. Many poor people resented this dependency culture and preferred to remain defiantly independent yet in need.

When one mentions “self-help”, one thinks immediately of Samuel Smiles: the moralizing concept of “self-help” seemed to be a value prized by the mid-Victorian middle class.